The Gospel of Yudas Read online

Page 3

‘Kuttiyaa—’ I would begin to blurt out the location of the head office in mortal fear.

‘Bah! Bloody rotten bitch! How many times have I told you! The first camp was in the inspection bungalow’s recreation club. We moved out a little later.’

He would help himself another shot of liquor, jiggle the towel tied around his head a little, dart fingers about his thighs to scratch a bit before he began to pace up and down in the room filled with the cloud of smoke. Soon he would begin retelling the pastoral beauty around the inspection bungalow, the terrifying solitude of the Kakkayam dam and the Konippara mountain watching over it like a sentry, piling on the seclusion and terror.

‘Do you hear me, you little imp? Whenever we had an inmate crouched over so that we could clobber his backbone to smithereens, the sound of each blow echoed right back to us from the mountain, crashing on to the powerhouse. You get it? That was as good as it got. It warms the cockles of my heart every time I think of it. The sound of the waterfall. Eerie nights taken over by the creepy cries of a million crickets. The howling wind. Oh! That was what policing was all about. That was what it meant to wear the uniform. Truly a golden age!’ My father would wipe his teary eyes and then say, ‘Now, where did we get the pestle rod?’

He was at my throat again.

‘Thoma—’ I would stammer.

‘Start with the initial,’ he thundered.

‘P.J. Thomas,’ I spewed it out like a parrot.

He was an employee at the powerhouse who lived close to the camp. The pestle rod had been brought from his kitchen. The camp was about a kilometre from the inspection bungalow. It used to be an old workshop surrounded by three bivouacs. Armed sentries manned the building. The quarter in the west led into a sprawling room where Parameswaran Saar and other top cops had their office. The fan brought from the bungalow ran all the time in that room.

‘Now tell me the name of the police dog in our camp?’

‘Shanti.’

‘Ah!’

My father would let me go, relieved that I could finally answer a question.

‘I should have named you after Shanti. It dawned on me only a little later. Ho! You haven’t seen her, have you? She was something!’

I would rub my bleary eyes and stare at him vengefully. My younger brothers were already halfway through their sleep. My mother yawned drowsily, grinding her teeth to mute curse words, while I strained to overcome the pain and angst by envisioning again the siege of Kaayanna police station. I was there with the thirteen rebels led by K. Venu. That was me among them, with a ponytail, wearing a long skirt and a blouse with puffed sleeves. Repeating to the captain: ‘I will stand up to anything. I am not scared of anyone. My body, I pledge it to the world. My mind, I pledge it to mankind. Ugh! If only the comrade could’ve helped himself with more weapons … He should’ve given a musket or two to his fellow fighters, been more careful with the kerosene lamp when it tipped over. Even better, he should’ve fallen over to shut out the fire with his own body before it began to blaze. He could’ve given an answer to this rotten world wallowing in darkness.’

Unbeknownst to the schemes of rebellion in my mind, my father would continue to brag:

‘You’ve got to work in the police force if you ever want to do a real job. Whack the hell out of people. Roll them up. Ha! Rolling them up. That’s what you call a real duty. The kind only real men like Parameswaran Saar and I could do. It was bodies we were rolling up, not wheat dough. Live human bodies! What is a human body? A bit of skin, some flesh and bones. Listen to me, you little brat! Do you have any idea how many men had their bones pulled right out of them with these very hands?

‘When you rolled them up, the inmates’ machismo would be torn apart,’ my father continued, letting out a chilling roar. ‘The men would cry. They would sweat in agony. Those who administer the pain sweat too. And as the pain grows so does the hardness of their perspiration. Salt. Salt from the sweat. It drips all over the floor and on their own bodies and then it dries and forms scabs. The skin slithers from the body, blood oozes out, and the flesh begins to crack and fall off. By now they are ready to admit to anything.’ Father twirled his handlebar moustache as he glared at me and said, ‘What do you all know? We made them throw up even the mother’s milk they had when they were little babies.’

When I look back and think about Yudas after all these years, I understand how my father’s homage to the torture camp could stir my own infatuation and adoration for Yudas. Only a subject of oppression would be able to recognize the grace of the fighter’s heart. Yet, who was he? No Das ever appeared in my father’s stories.

When my father called his name out at the shore as Yudas pulled up Balu’s body, the people around us gawked at him. Das who? ‘He is Das, the fourteenth insurgent, isn’t he?’ My father queried, shaking all over. Years of addiction to alcohol and ill health had diminished my father into no more than a skeleton.

Yudas raged like a smouldering fire poked out of ashes. His mouth and nose reeked of marijuana.

‘I am not Das!’ he yelled as he lunged towards Father. ‘I am Yudas. Judas, the betrayer. He that is faithful in that which is least faithful also in much.’ He grabbed the rattling skeleton that was my father and shook him wildly. ‘He who is cowardly with only a little is cowardly also in much.’ I really thought the violent shaking would end my father’s life right then. For a moment I hoped he would throw my father’s weakened body into the deep end of the lake. Had the mob around them not intervened, it could’ve happened. Yudas suddenly let go of my father who tottered about and struggled to regain balance. He pulled Balu’s body with manic force on to the shore where it fell with a thud. Then he turned back and he threw himself on to the expanse of the lake like a fishing net. The swelling water soared as it made way for his abrupt departure, washing Balu’s body back and forth in the water like a plantain stalk. I would never forget Balu’s face. Chromides had nibbled it into a pitted human coral. I took great care to burn numerous incense sticks when his body was taken home, draped in white sheets and laid on the floor for funeral rituals. My father sat looking at him keenly, his head quivering. I was thinking again of Yudas while Balu’s mother, my aunt, wailed. Yudas too was crying as he swam back into the lake and vanished out of sight.

I racked my brain trying to figure out who Yudas could be. Thirteen of them had laid siege to the police station. There had been no Das. I don’t recall my father ever mentioning a nickname for Apputty or Little Rajan or Pushparajan or even Bharathan that sounded anything like Das. Who, then, was Das? I had to find the answer to that question. I was thinking tenderly of the fourteenth rebel who couldn’t find a place in history. The more I thought about it, my love for him grew. When Balu’s body was lowered into the funeral pit in the south end of our yard, I was watching the lake. In my heart my passion for Yudas surged. Light began to fade in the dusk and a dense green hue adorned the lake. I yearned to feel his pale face in my hands, caress the crimson shimmer in his long hair, and the overgrown, unkempt beard and moustache that made him look like Jesus Christ. I kept gazing at the middle of the lake. Could he be still lying immersed in the lake? I remembered how frantic his face had seemed. His eyes were bloodshot. His crimson-streaked hair was wet and glued to his scalp. He had unleashed a wild force in the waves when he swam away for the last time, which made me wobble and trip up although the water was only ankle-deep where I stood. Night fell on the lake while I kept my vigil, followed by the arrival of the moon. The water shone bright in the moonlight. Longing for his love, I looked everywhere for a glimpse of Yudas’s shadow.

It was only after visiting the abandoned hut the next day that I was certain that Yudas was gone forever. The shack had been left open. Its interior was bare but for a small desk and a makeshift cot. All the other belongings—mudstained clothes and towels and the little chest were gone. I stood there feeling an inexplicable loss. I didn’t know what to do for a while. Fearing for the worst, I wondered if I would ever get another

chance to escape from my bleak world. I would’ve loved him with all my heart, adored him and set out on the path of revolution. At fifteen, for the first time in my life, I endured the pangs of lost love, separation and the emptiness of letting go as I trudged the long walk home.

My father’s condition had worsened by nightfall. He let the doctor know that he was knocked around violently by Yudas the day before. The doctor wondered why anyone would do such a thing. My father smiled at him with his trembling head and said: ‘That son of a bitch! I’d tortured the shit out of him. Even the roller bent when I put him under it. He wouldn’t say a word in the beginning. But I made him sing. He crooned whatever he knew by the time we broke his rib cage, just like a canary. Thanks to him, we dumped two of his mates in the gorge.’

In the porch beyond the half-walled entrance of my house, stalks of plantain with incense sticks stuck in them were strewn around behind Balu’s head. The sight seared my heart. I began to have a recurring nightmare in which I flailed about in the deep end of the lake while my legs went limp. Many corpses lying with arms folded at the bottom beamed at me. All of them had Yudas’s visage.

THREE

I met Yudas again on the banks of the River Kallai, far north from my village, but not until five years later.

I was in Kozhikode, attending college for a postgraduate diploma certificate. It was a novel branch of education at the time. Hitting the road to Kozhikode was my way of being as far away from home as possible. Until then, each year, I had expected Yudas to turn up any day. I would wake up every morning looking at the lake and thinking that the minutest speck on the surface could turn out to be him.

My father’s situation had become miserable. Mother passed away, drowning in the lake. It happened while I was at the college hostel. That day my younger brother had hollered, looking for Mother, but she didn’t respond because she wasn’t home. In the evening, chromide hunters at the lake caught her long hair. They pulled out her blistered body as though it was a giant chromide hidden amidst the crevasses in the mud. With the exception of our enormous dilapidated Naalukettu, Amma’s cousin, the illicit lover, had taken away all our properties. Father remained in the house stuck in his bed. I rarely visited home.

Those were awfully difficult days for me. I felt like a rubber doll tossed into the water, bobbing up and down and drifting away with a sense of foreboding. I thought of Yudas every night. His memory agonized me the more I thought of him. Sometimes I hated him. I didn’t think he really deserved my love because he gave himself up after being subjected to torture by my father. He was a coward. He put up nothing but deception. But wasn’t I deceiving myself as well? Didn’t I blow everything out of proportion to create a hero out of a coward? It was my fault. Love was an absurd emotion, especially if it was meant for a man. What was really needed was love for humanity. I felt guilty of violating the purity of my mind, having fallen for the wrong kind of love during the best period of my life. To atone for this, my mind returned to Kakkayam camp perpetually, submitting myself to the torture sessions which my father celebrated. I bit my teeth and pursed lips as I imagined yelling ‘Victory for the Revolution’ or ‘Power to the Naxalbari’. Such whimsical illusions were all that remained in my generation. Everything else had vanished. My father’s generation savagely subjected the youth of my age to roll-up routines until they purged the young things’ audacity and grit to love, trust and fight. I prayed ardently to reclaim the strength to at least have trust. But no, my generation can never believe unless they feel the gashes from the nails with their bare hands.

I went to the river along with the rest of the students from my class when the news of a classmate’s death by drowning broke out in school. He had participated in an agitation opposing the pollution of the River Chaliyaar. Later on there were rumours suggesting that this might have been the reason he was killed. It didn’t really bother me much. Someone was dead. Someone had killed. That’s all there was to it. But when I heard that the body had not yet been found, I was reminded of our lake. I felt nauseous standing at the edge of the wide river. A wave of memories rose in my mind. Many in the crowd took to boats and canoes in search for the body. Suddenly a man emerged from below the surface of the water with a dead body as though he were a heron breaking out of the river after catching a flapping pearl fish. Water sprayed everywhere. The man transferred the body to the boat and swam back into the river. I recognized him from the first glimpse. My heart skipped a beat. I held myself back having begun to yell ‘Yudas!’ I wondered if he’d announced ‘Long Live the Revolution’ when he was done! Did he holler ‘Naxalbari Zindabad’ or dare them with the jibe ‘Arrest me if you have the nerve?’ Did I hear him say that? I was too far away to see or hear him clearly. I wanted to throw myself into the river and swim up to him. As I looked on he vanished beyond the waves.

Standing there, I felt let down being a woman. In that moment I loved Yudas with a greater intensity than I had when I was a fifteen-year-old. While walking with the group headed to the dead boy’s home, I thought about Yudas. He was lost from a distance. His crimson-streaked hair, a pale face and melancholic, languid eyes had flown away in the river. The wailing mother of the dead boy looked like my paternal aunt. It must have been a long time since I had last seen or even heard about someone whose life was claimed by water. After a long time, I inhaled the smoke from the incense. I saw the whitish toes of the feet swollen by water when we put a wreath on the dead body. An afternoon spent swimming in a lake, precipitated under a blue sky, haunted me. I knew I had to meet Yudas. Suddenly, my resentment for him evaporated. I was anxious to find where he had gone beyond the river. Even after all my classmates had left I hung around, as though I had swallowed the hook from a fishing rod. I wandered around for a long time on the shore. In the end I found his place. He lived by the far end of the river in a shanty cobbled out of coconut leaves. I entered his shack after washing my feet, soiled by all the tramping I had done along the muddy shoreline. I was exhausted.

He was drinking. Seeing me in his house startled him. But he didn’t smile until he finished what was left in the bottle. I couldn’t even utter a word as I fought the emotions raging within my mind. I clutched the bag hanging from my shoulder, tugged at the edge of my sari and stared at him with a sweaty face. He got up slowly to pull off a shirt from the wall, and did the buttons one by one before turning towards me.

‘You must be Prema?’

His voice was lifeless. My voice was stuck in my throat. Yet my heart was overjoyed to know that he recognized me after five years.

‘What are you doing here, Prema?’ he asked in a flat even tone. My voice failed to come out. After a long time I asked him what he was doing there.

Yudas smiled apologetically. ‘I have been living in the area for a while now. I do think about your village sometimes. I think of you too. I even thought of paying a visit once. But I fell sick when I was about to start. How could I then? You have seen for yourself. I am busy here every day. Someone will die drowning each day.’ He spoke about this and that as though we’d met for a routine conversation. My heart was pounding. I couldn’t take my eyes off him. Yudas, ‘Croc’ Yudas. The revolutionary who’d recovered corpses from my lake. The champion of my liberation struggle.

‘Come inside,’ he said. The room reeked of ganja. I felt it was making me high. I asked myself why I had to come so far to find him. What was there between us? What did he mean to me? Nothing! Yet I couldn’t let him go. I sat on the bare floor. I told him I didn’t think he would recognize me. He too said he didn’t expect to see me here. He pulled out a matchbox nestled in his lungi, and lit the kerosene stove. He washed a handful of rice, poured some water into a pot and waited for the flames to turn blue. The fire blazed red, then yellow and finally became blue. Then he placed the pot on the stove and began to talk slowly, like how water takes its time to boil over.

‘The river is nothing like the lake. Its current is quite wild. There will always be something floating on it, come s

ummer or monsoon, mostly tree trunks, coconuts, sometimes even animals. You can’t blame the river for the current. It’s the humans who ought to be blamed. They cut down all the trees on the mountains, let the soil go loose. Some rivers have dried up and some others have become little gorges. Yet man is not done with them. He will dig out the sand; encroach upon the shorelines. Hmm … It may seem like nothing more than water, but when pushed to the brink, it can destroy everything!’

I was getting impatient.

‘Das …’

‘Yu–Das …’ he corrected me.

The pot was warming up. He sat motionless, watching the steam. Suddenly, I was mad at him. I moved beside him and leaned on his shoulders. His moustache and beard glowed blue in the light from the stove. I yearned for a hug from him. But he didn’t move. He didn’t even look at me.

‘I waited for you all these years.’

My voice was morose.

‘Why?’ he asked. He sounded like he was frozen, deep inside the water, and that his form was now dissolving. My anger got the better of me. ‘Das?’ I yelled. ‘You couldn’t read my mind? I need you to love me. I want to live with you.’

‘For what?’ he mumbled like a fool.

I didn’t have an answer. He did have a point. What did I love him for? What was it that I wanted when I live with him? An orphan who dives to recover dead bodies with no more than a nickname: ‘Croc’! Why in the world would any woman, young and full of life like me, even fall for a man who reeks of the stink from the dead? I leaned further on his chest languidly. He continued to stare at the stove, faking a smile. I was going crazy in my torment and despair. I told him things that even I wasn’t paying attention to: ‘Listen! Don’t you remember the afternoon that day? We spoke about a lot of things and we were soaking wet. Have you forgotten that you taught boys about girls? Didn’t I kiss you? Didn’t you have feelings when I touched you? Tell me the truth, Das. Aren’t you aroused by the woman in me?’

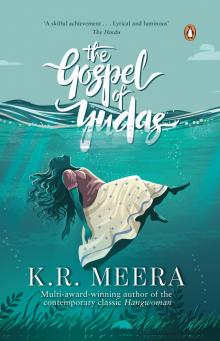

The Gospel of Yudas

The Gospel of Yudas Hangwoman

Hangwoman